As part of the successful completion of my Masters MSc in Data Analytics (Distinction awarded December 2021), I completed research for my dissertation: Exploring the application of Machine Learning techniques of NLP for Text Classification to Predict the Outcomes of Human Trafficking Criminal Prosecutions. I built and trained my text classification models based on court case fact summaries available in the UNODC Sherloc caselaw database.

Following the completion of my degree, I was invited to present my dissertation work to the Oxford Brookes University Migration and Refugees Research Network in March 2022.

Abstract

As methods in Artificial Intelligence (AI) have advanced rapidly in the last two decades, many in law enforcement and the legal domain are increasingly turning to predictive analytics to combat and prevent Human Trafficking and other crimes, streamlining policing and the criminal justice system through the application of machine learning technologies. Legal Judgement Prediction (LJP) is a sub-field of predictive analytics research within the legal domain which uses Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques to build classification systems in order to predict the outcomes of court cases. From 2014 a range of Supervised and Deep Learning methods have been successfully applied to LJP problems with model performance accuracies ranging from 69% to over 96%. In this paper, the application of proven NLP techniques and Supervised machine learning classification algorithms are explored in order to predict the court judgements of human trafficking criminal case summaries extracted from the online United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) Sherloc case law database.

Initial experiment results indicate that Legal Judgement Prediction can be successfully applied to a diverse dataset comprised of case fact summaries from several countries when restricted to a particular area of case law or crime type. Both the Linear Support Vector Machines and Random Forest models employed in this paper were able to correctly predict 75% of court case outcomes when applied to a balanced dataset, comparing well with other recent LJP studies. However, despite promising results, the ethical risks of bias, privacy and data protection cannot be overlooked. Consideration of the purposes of predictive analytics and whose interests and priorities are being served in developing these technologies must be continually interrogated. Algorithms which can successfully predict court judgements in criminal cases, even with a high level of accuracy, will remain useless if they continue to operate inside wider systems of societal and economic inequality.

Methodology

Tools and Resources

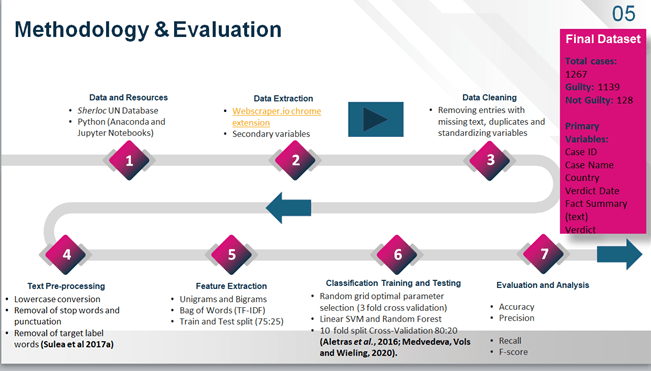

For comparability with previous studies, Python was the primary programming tool used to clean and pre-process data, extract features and train the selected classifiers. Where final coding and library package recommendations have been made available in prior studies, these were adapted to formulate the coding for the experiments in this project. The dataset for these experiments was collected from the online UNODC Sherloc case law database using a chrome extension web scraping tool called webscraper.io. Although there are methods to web scrape data from online html formats through Python, such as the Beautiful Soup package, due to time constraints and the learning curve required it was determined that an automated web scraping tool would be the most effective choice to gather the required data.

Data Extraction

Choosing the best automated web scraping tool did present some serious challenges. Firstly, the Sherloc database website used an infinite scroll pagination method that was not compatible with many of the most commonly available and free web scraping programmes. Also the links for each case entry leading to additional information on a new page were not based on unique URL extensions but instead appear to be Java Script Object Notation (JSON) based API calls, which query and retrieve information directly from a website database upon request (Tamuliunaite 2021). Again many of the most basic web scraping tools could not manage the required command to scrap secondary variables from the subsequent linked case pages. Alternatively a sample of secondary variables for both classes was manually extracted for 128 not guilty and 128 guilty cases, allowing for exploratory analysis of these categorical variables for any potential useful patterns or insights. However in future, an improved web scraping method should be explored to collect these additional variables for the entire dataset of 1267 cases to provide for more complete data exploration and understanding. An example of the original data format on the Sherloc website and the subsequent representation of this text after web scraping can be found in Appendix 7.

As previously noted, while completing the 5% manual review of the scrapped data to ensure accuracy, it was discovered that many of the cases categorized as not guilty were in fact guilty in regards to human trafficking related charges while not guilty in instances of other charges, such as money laundering or fraud. Unfortunately this required a fully manual review of all 242 not guilty cases, which resulted in 114 cases being reclassified as guilty. In some instances, court cases resulted in initial acquittal and later conviction or vice versa on appeal. It was decided that any case which either initially or at appeal resulted in a verdict of not guilty at some point should remain labelled as not guilty for the purposes of this project. Also where the human trafficking related charge or charges applied were not clearly stated, discretion was used to make the determination. For example ‘people smuggling’ or ‘pimping’ was not classified as a human trafficking law based charge, while charges such as ‘forced prostitution’ and ‘forced labour’ were considered sufficiently similar for inclusion. This occurred rarely and usually only in the instance when a country did not have any human trafficking criminal legislation passed at the time of the court case proceedings (mostly cases dating from pre and early 2000s). The dataset was cleaned of any cases with missing text or in a few instances duplications using Python. Also any text summaries which were not automatically translated into English by the online database were excluded. Ultimately there were only 128 not guilty usable cases from the database and 1139 guilty cases. The extreme imbalance in this dataset between the classes will be addressed further in the experiments section.

The final full dataset for text classification includes human trafficking criminal court cases from 69 different countries and consisted of the following variables: Case ID, Case Name, Country, Verdict Date, Fact Summary (text) and Verdict (class: guilty or not guilty). Additionally 128 guilty and 128 Not Guilt cases also contain the following additional variables: Victim Type[1] (Male, Female, Both, Child), Defendant Gender (Male, Female, Both), Defendant Nationality, Primary Trafficking Type, Secondary Trafficking Type (if applicable), whether the crime was Transnational or Domestic and the contributing Institution or Organization. See also Appendix 5 to view the full dataset and Appendix 7 for more details on the full variables list.

[1] Though some cases have numerous victims and defendants, due to time limits the data extraction will focus only on the first two listed victims and defendants in each case.

Text Pre-Processing

Initial exploration of the full dataset shows there are 152,122 words comprising all ‘Fact Summaries’ from the guilty class, 14,894 of which are unique. For the not guilty class there are 12,736 total words, of which 3,412 are unique. However many of these words may have little useful predictive meaning and reducing the total number of potential unique features is an important step in the text classification pipeline. After cleaning to remove duplicates and any entries missing text, several of the previously discussed pre-processing techniques were employed in Python in order to reduce the dimensionality of the final text before the feature extraction stage. The text was converted to all lowercase, and a pre-populated library of the most common English language stop words from Python called NLTK was used to remove words unlikely to contribute any feature weight in the class prediction algorithms, such as ‘I’, ‘me’, ‘to’, ‘and’ etc.… Punctuation, possessives (‘s) and leftover remnants of html language picked up by the web scraper were also removed. Per the research conducted by Sulea et al, the following target (class) labels and related terms were deleted: ‘guilty’, ‘not guilty’, ‘acquitted’ and ‘convicted’ (2017a).

Feature Extraction

A binary coding was used to simplify the class labels for the algorithms, with 0 for not guilty and 1 for guilty. A simplified form of the full dataset consisting only of the ‘Fact Summary’ text and classification labels was then created and split into training and testing sets, with the text as the ‘X’ variable and the label as the ‘y’ variable (i.e. X train, X test, y train and y test). A train test split ratio of 80:20 was used. An inbuilt Python Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) algorithm was used to vectorise the text features of the training and testing sets and extract weightings based on the Minimum and Maximum parameter ratio, which was set at 10:1 with a maximum limit of 800 features. It is important to note that these parameters were selected based on the literature and a range of parameters could have been set to increase the maximum number and potential weighting of extracted features.

Although the initial project proposal indicated a plan to extract a range of words and phrases from unigrams to quadrigrams (1:4), the vectorizer only produced output of unigrams and bigrams. This is not surprising given both the low parameter set limit of 800 features and the fact that, as noted by Medvedeva, Vols and Wieling, longer n-grams or phrases are less likely to occur in fact summaries, leading to no significantly weighted vectors beyond bigrams in this instance (2019). Therefore trigrams and quadrigrams were not used as features for the prediction of classes for the purposes of this paper. The final shapes of the training and testing matrices were 1,013 cases x 800 features and 254 cases x 800 features.

Experiment Parameters

Using a random grid search method to find the optimal parameter settings for the SVM and Random Forest classifiers, tenfold cross validation with a 75:25 ratio split for training and testing was then employed to fine-tune the final parameter choices for the best fitting predictive models. This is the same method employed by a majority in the literature for Supervised learning algorithms and will allow for better comparability of results with previous research (Aletras et al., 2016; Medvedeva, Vols and Wieling, 2020). K-Fold cross validation improves the generalization of machine learning classification models and reduces the risk of performance results being based only on a specific combination of fact summaries. The first round of experiments utilized the full, unbalanced dataset of 1267 court case text summaries. The second round of experiments used a subset of the original dataset, which combined the 128 not guilty cases with 128 randomly selected guilty cases to create a balanced dataset. The same parameters were then used for the TF-IDF feature extraction and again a ten-fold cross validation was used to find the new optimal parameters for each machine learning classifier. The optimal parameters selected through use of a random grid search and ten-fold cross validation of the training set for both classifiers in Experiment 1 and Experiment 2 can be found above.

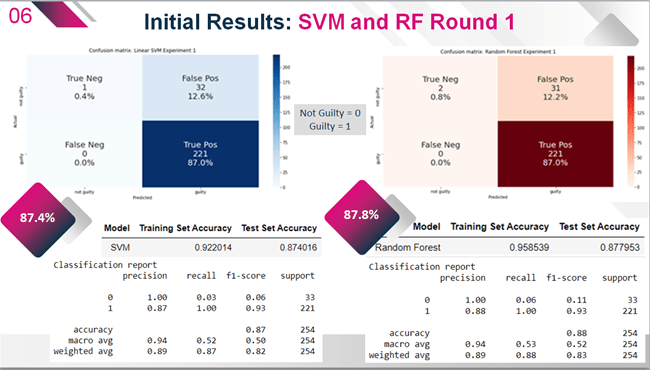

Experiment 1: Initial Model Results

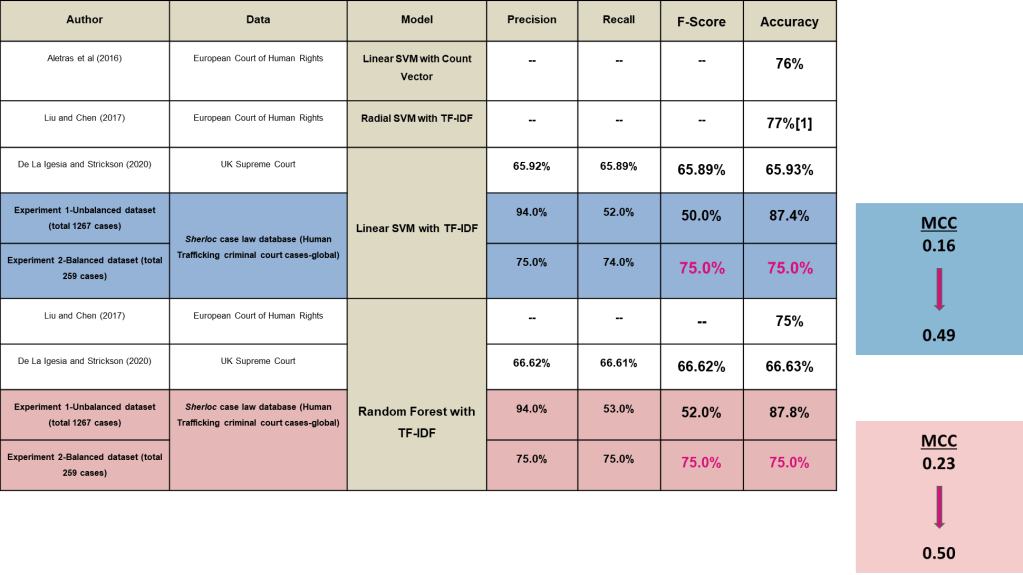

Initial results seen in above from both the Linear SVM and Random Forest models showed reasonably good overall accuracy after testing at 87.4% and 87.8% respectively. However further examination of the Precision, Recall and F-score metrics in the model classification reports exposed a serious problem with incorrect classification of cases labelled as not guilty. A very strong F-score of 93% correctly predicted guilty cases had masked this problem in the overall model accuracy, underscoring the importance of the other metrics for performance evaluation. Upon further analysis, the F-score for the SVM model indicated that only 6% of not guilty cases from the testing set were correctly predicted as not guilty, while the Random Forest model performed only marginally better at 11%. The recall values for this class were also extremely low at only 3% and 6% respectively, contributing to the low F-scores. Despite this, the Precision for not guilty cases is 100% for both models, indicating that these algorithms are both robust against False Negatives (instances where guilty cases are incorrectly labelled as not guilty). Both models correctly predicted all guilty labelled cases as guilty, with a recall value of 100% and a nearly equal precision of 87% for the SVM model and 88% for the RF model.

As the first round of experiments were completed with a significantly imbalanced dataset skewed towards the guilty class, the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) was also calculated to better reflect model performance as an alternative to Accuracy. Initial results indicate that the balance of performance across the classes is quite low with an MCC of just 0.16 for the SVM model and 0.23 for the RF model. This is unsurprising given the previously noted low recall and F-scores for the not guilty class (negative class).

Analysis

Consideration of the acceptable risk levels for innocent defendants to be convicted and for guilty defendants to be acquitted will clearly depend on who is developing these systems and how they are applied in the real world. From an ethical and social justice perspective, particularly given the previously noted issues with bias in data and AI, the risk of a high False Positive rate is significantly greater than a high False Negative rate. In the case of both models in this first round of experiments on the unbalanced dataset, the False Positive rate is extremely high. As seen in the confusion matrices (Figure 21) below, 32 out of 33, or 96% of the actual not guilty cases were mistakenly labelled guilty by the Linear SVM model. The RF model did not perform much better, with 31 out of 33 or 93% of not guilty cases incorrectly predicted as guilty. In a real world scenario, though these models ensure that 100% of guilty defendants are convicted, they also would mistakenly convict well over 90% of potentially innocent defendants.

Potential Contributing Factors

As noted in the Data Extraction section of the Methodology, the full dataset is extremely imbalanced between the classes, with over ten times more guilty labelled cases as not guilty. This could be one of the reasons behind such a low recall score for the guilty class, which only provided a total of 128 cases for use in model development and testing. It may be that a more balanced dataset would reduce the disparity in recall scores between the classes. A high overall accuracy score is useless for model generalization in this case if it cannot provide reasonable robustness of recall between the classes as new data is introduced.

A second potential issue affecting the results could be the steps taken to set parameters for feature extraction. In future using a random grid search and K-fold cross validation to find the optimal parameters for the TF-IDF function, such as feature limits and maximum and minimum document frequencies, might also improve the overall performance of the predictive models by fine tuning the feature weightings. A final consideration is the data source itself. Most law enforcement and criminal justice systems have in place their own applied rules or processes for deciding which cases should be prosecuted and brought to trial. This includes balancing likelihood of conviction with the cost to the public, among other factors (The Code for Crown Prosecutors, 2018). For perspective, 2019 statistics show that about 83% of crown court cases which go to trial lead to conviction of some or all charges (Criminal Justice Statistics Quarterly: December 2019, 2020). In the USA, the conviction rate is nearly 99% for federal criminal trials (Doar et al., 2021). As all of the case summaries obtained from the Sherloc database for these experiments derived from prosecuted court cases, it may be that they are already skewed towards conviction. This could mean that the fact descriptions and therefore text elements of these cases are more similar than different and could be contributing to issues with models correctly determining not guilty cases. Analysis of the top weighted features (unigrams and bigrams) for each class in section 5.4 will further explore this possibility.

Due to the limited scope of this project it was decided that the parameters for the TF-IDF vectorizer would not be adjusted at this time and instead experiment 2 would focus on determining if the imbalance of the dataset was a major factor contributing to the low F-scores for the not guilty class. Keeping the feature extraction parameters the same will also allow for better comparison between the experiments by controlling for one variable change at a time.

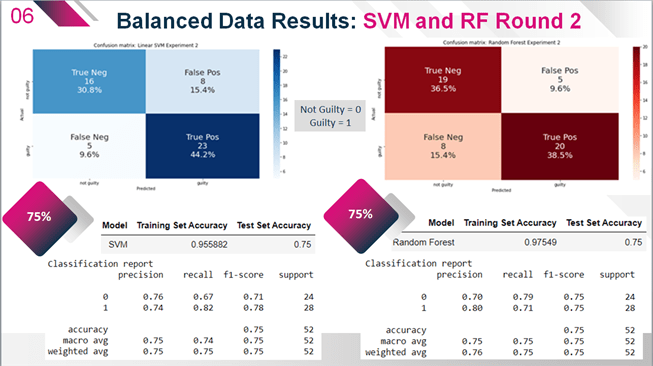

Experiment 2: Balanced Subset Model Results

128 guilty labelled cases were selected using a random sample function in Python and combined with the 128 not guilty cases to create a balanced subset of the full dataset. As before, an 80:20 ratio was used to randomly split the data into training and testing sets. The same parameters were then used for feature extraction of unigrams and bigrams with the TF-IDF function. It should be noted the final optimal parameters for the balanced dataset classification models were slightly different from those for the unbalanced dataset in Experiment 1. The chosen models for both Linear SVM and Random Forest produced lower overall testing predictive accuracies of 75% (see above). However the recall and F-scores, though lower for guilty cases than in Experiment 1, were much higher for not guilty cases and significantly more balanced between the classes. As seen in the classification reports for both models (see above), the F-scores for not guilty cases jumped to 71% and 75% for the SVM and Random Forest classifiers, with a recall showing correct prediction of this class increasing to 67% and 79% respectively. Though this was accompanied by a reduction in the F-scores for the guilty class to 78% or 82% recall and 75% or 71% recall respectively, these results indicate that the overall robustness of the models has improved.

Though more often employed to evaluate performance on skewed datasets, the MCC also supports these results showing significant improvement in the balance of performance between the classes, with nearly equal scores of 0.49 for the linear SVM model and 0.50 for the RF model.

Analysis

The results of this second set of experiments strongly supports the hypothesis that an unbalanced dataset was a large contributing factor to the low recall and F scores for not guilty cases in both models. Using a balanced dataset ameliorated this problem, although it did also reduce the recall, precision and F score of the guilty class. However 75% is still significantly above the threshold of better than simple probabilities (50/50) and is impressive given that these case summaries were collected from over 69 different countries with varying legal systems and human trafficking laws, as well as enforcement practices. Most importantly, using a balanced dataset appears to have significantly reduced the occurrence of False Positives in both models. As seen in Figure 24, the linear SVM model reduced the percentage of potentially innocent defendants being convicted from 96% down to 33%. The Random Forest model performed even better, reducing this rate from 93% down to 21%. Although these are still unacceptably high error rates for False Positives, the improvement is significant. This reduction in False Positives did come at a cost, with an increase in the False Negative rate from 0% in the first experiment to 18% for the SVM model and 28% for the RF model.

Top Weighted Feature Analysis

As highlighted in the Experiment 1 results Analysis section, one of the potential causes of such a low predictive accuracy for the not guilty class, or rather the tendency of the models to categorize almost every single case summary as guilty, could be due to a high level of similarities in the case summaries themselves, and therefore the extracted features (unigrams and bigrams). Using Python to extract and examine the top ranked unigrams and bigrams, it is possible to see which features have been given greater weight in the predictive systems and determine any text that may be clearly indicative of similarities or differences between the classes.

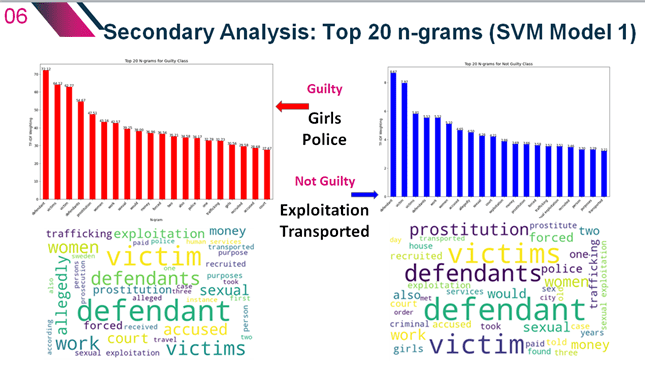

Above show the top 20 n-grams for each class based on the feature extraction matrix coefficient weightings. These were extracted from the full dataset weighted feature matrix created in Python for Experiment 1. Interestingly all but one are unigrams, reflecting previous studies which have generally found unigrams and bigrams to be the most important features extracted using the TF-IDF method. As 14 out of the 20 top weighted n-grams are the same between the classes, albeit with differing rankings, there is some evidence supporting the hypothesis regarding similarity in case composition (and therefore text description) as a reason for some of the misclassifications by the models. It also appears that several of these n-grams might be redundant and should have been considered for removal in the pre-processing stage as they could either be considered without any real interpretable meaning or could even be confounding the results as they are too closely related in meaning to our class label outcomes. This includes n-grams such as ‘allegedly’, ‘accused’, ‘defendant’, ‘defendants’, victim, ‘victims’, and ‘court’. Additionally words such as ‘also’, ‘one’, ‘two’, and ‘would’ could be included in the stop words list for better dimensionality reduction. However a few potentially interesting differences have emerged, with the unique inclusion of ‘girls’, and ‘police’ as top n-grams for guilty case summaries and ‘exploitation’ and ‘transported’ for not guilty cases. Figure 27 shows these top n-grams in the form of Word clouds for better visualization between the classes.

Further analysis by sector professionals could prove useful in better understanding any significance to these n-grams. However initial conjecture might be that cases are more likely to result in conviction when related to ‘girls’ or minors where the defence argument of consent is null and void in most human trafficking law. Equally this may be the case when there is more involvement with or evidence provided by the ‘police’ as part of a prosecutor’s case. Whereas the high ranking of ‘exploitation’ and ‘transported’ to predict cases as not guilty might suggest that cases where the line between human smuggling or labour exploitation and human trafficking laws are more blurred result in less human trafficking convictions. It could be interesting to explore if there was in fact conviction on other charges in these instances.

Comparison of the top 20 n-grams extracted from the balanced data subset with those extracted from the unbalanced full dataset shows an almost identical list of unigrams and bigrams. As the balanced dataset was a smaller subset of the full dataset, this is not necessarily surprising. This further suggests that having a balanced amount of cases between the classes for model training is the key to improved prediction for both classes, although in this instance it has not provided any illumination as to the importance of the top weighted words and phrases for each verdict. A much larger balanced dataset may provide more distinct and useful features for further interpretation in future experiments.

Comparative Analysis and Considerations for Future Research

This project has shown promising evidence that Legal Judgement Prediction techniques using Natural Language Processing can be successfully applied to a diverse dataset comprised of case fact text summaries from several countries when restricted to a particular area of case law or crime type. Despite a range of differing court systems, human trafficking laws and enforcement policies, both the Linear SVM and Random Forest models were able to correctly predict 75% of court case outcomes when applied to a balanced dataset. This compares well with other studies which have used linear SVM models with count vector or TF-IDF for weighted n-gram feature extraction to predict court decisions.

As can be seen in above, the experiment results in this paper have matched the average accuracy of 75% achieved by Medvedeva, Vols and Wieling and 76% by Aletras et al in comparable studies which used a dataset of court summaries (Circumstances) from the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). Liu and Chen (2017) also conducted LJP experiments on the ECtHR dataset, which showed an average overall accuracy of 77% for a radial SVM model and 75% for a Random Forest model. In some instances the results in this paper have surpassed other examples in the recent literature, including a study in 2020 by De La Iglesia and Strickson which used court summaries from the UK Supreme court in binary LJP experiments, achieving a lower overall accuracy of 65.9% and 66.6% respectively for linear SVM and Random Forest models. Though there have been studies which were able to achieve significantly higher Linear SVM and Ensemble SVM model accuracy of 96.9% and 98.6%, these were multiclass problems (6-8 classes) and were based on French language text of court cases from the French Supreme Court (Sulea et al., 2017a). Therefore these are not directly comparable to the experiments conducted in this paper.

Using an unbalanced dataset in the first round of experiments produced even better overall accuracies of 87.4% and 87.8% for the Linear SVM and Random Forest Models. However as previously discussed this was misleading and did not actually reflect the extremely low predictive F-score for not guilty cases for both algorithms. As expected, the results of the second round of experiments using a smaller but balanced dataset improved the consistency of predictive accuracy across both classes while still maintaining a reasonably strong accuracy of 25% better than simple 50/50 probability.

As noted in previous studies, n-grams (in particular unigrams and bigrams) were found to be most useful as features for the chosen TF-IDF technique. Additionally, pre-processing the text to remove punctuation, classification label words, stop words and lowercase conversion all appear to have been useful steps, although future experiments should also compare different combinations of techniques to see if these hinder or improve results. It is clear from the analysis of top weighted features that more pre-processing should be done to remove words with adjacent meaning to the target class labels such as: ‘defendant(s)’, ‘victim(s)’, ‘allegedly’ and ‘court’. The inclusion of these words could be skewing the results of the models. Also some words that should be considered stop words with little meaning were not sufficiently excluded. In future the top n-grams of the full corpus could be examined to develop a more exhaustive list of words for removal from the final text before the feature extraction stage. This could help to reduce any confounding features which might be leading to model training based on spurious correlations (Muaz, 2021). Finally, during the feature extraction stage a random grid search could have improved the parameters for the TF-IDF feature weighting process, resulting in more fine-tuned feature data for use in model training. This step is recommended for any future experiments with this dataset.

In much of the current literature which employed SVM, Random Forest and other Supervised learning algorithms for LJP, court case datasets were broken down by the relevant area of law or Human Rights Article involved before feature extraction and model training was completed. Results were them combined for an overall average model accuracy across these subcategories. Although the dataset used in this paper is already focused only on human trafficking crimes, it may be that future experiments with a sufficiently large number of cases could split the dataset further by trafficking type (i.e. Sex, Labour, Domestic Servitude, etc.…) and examine any changes to the predictive performance of the models based on this further narrowing of the scope of the corpus used for model training. This might also allow for more meaningful and targeted analysis of the top weighted features for each category. It should be reiterated that several assumptions were made to develop a method to accept or reject cases labelled as not guilty for use in the final dataset, as described in the Data Extraction section of the Methodology. This was due to a lack of consistency, clarity and accuracy in the available online database. These assumptions may have allowed a level of subjectivity into the labelling process which might have impacted on the performances of the final models. Therefore caution should be used when citing these results, until additional experiments can be conducted using a larger dataset. Future research should attempt to expand this dataset in order to improve understanding of the model performances discussed in this paper, as well as explore other variables whose significance may have been obstructed by the small sample size. Ideally this would be a balanced dataset with a minimum of 1,000 cases for each class. An improved web scraping method using Python could also be designed to increase the number of variables collected in addition to the main text and labels.

Conclusion

All of the proposed research aims and objectives outlined in the Introduction to this paper have been achieved with potentially significant implications for ongoing research into Legal Judgement Prediction using Natural Language Processing for Text Classification. Firstly, results from both sets of experiments overwhelmingly support the primary aim of this dissertation, which was to determine whether previous LJP outcomes could be comparably replicated using a new dataset of court case fact summaries specifically focused on the prosecution of human trafficking crimes. The research conducted in this project evidenced that LJP machine learning models could be trained to generalize to legal datasets from multiple countries and court systems without sacrificing performance accuracy. As part of the secondary research aims, examination of the top weighted n-gram features extracted for model training showed that the use of Supervised machine learning methods which allow for consideration of the reasoning behind system decisions is important for assessing the legitimacy of these AI technologies in the real world. In future, further review of these top weighted words and phrases by legal and law enforcement professionals might provide additional insight into the potential usefulness of this information.

The implications of using AI predictive technologies were reviewed in the literature and discussion of the ethical risks associated with data bias, security, privacy and transparency were interrogated as part of the primary objective of this study. Though overall model results were significantly above the rate of simple probability for correct verdict predication, this was accompanied with serious risk of False Positives in the first set of experiments. Nearly all not guilty cases in the first round of model training and testing were incorrectly labelled as guilty, leading to very low recall and F-scores for this class despite high overall predictive accuracies of 87.4% and 87.8% respectively for the applied linear SVM and Random Forest methods.

Using a smaller but balanced subset of the data in the second round of experiments, a significant reduction in this risk of False Positives was achieved, albeit with lower recall and precision for the guilty class and an overall lower predictive accuracy of 75% for both models. The Linear Support Vector Machines and Random Forest models employed in this research performed nearly equally well in both Experiment 1 and Experiment 2, although The RF model appears to be more effective for correct prediction of the not guilty class, while the Linear SVM model performed slightly better for the guilty class. It may be that future experimentation should include testing a stacked generalization of the two algorithms into an ensemble model, as this might yield higher overall accuracy while maintaining the improved balance of performance between the classes (Brownlee, 2020).

For the secondary objective, a usable XLSX formatted dataset of human trafficking criminal court case text ‘Fact Summaries’ was created through web scraping of the UNODC Sherloc online case law database. Beyond the outcomes of this project, the more accessible dataset will allow for future research into Legal Judgement Prediction and human trafficking case law as well as support attempts to replicate the experiments described in this paper.

Recommendations for future research include the need to train and test the machine learning models on a much larger, balanced dataset of court case summaries. The second set of experiments supported the hypothesis that a balanced dataset significantly improves performance of the models between the classes, with more equal recall, precision and F-scores. However there continues to be a lack of accessible, text rich data on criminal court cases generally and human trafficking specifically at the required scale for suitably robust Machine Learning analytics. Research partnerships with statutory agencies and Non-governmental Organizations (NGOs) could provide the additional data resources at the required scale and should be investigated as a way to address the general lack of publicly available datasets for LJP.

Further experimentation with the best combination of text pre-processing methods for better text cleaning and use of a random grid search to determine optimal parameters for the TF-IDF vectorizer should be reviewed as ways to improve feature extraction and therefore model accuracy. As noted in the Project Issues and Mitigation section, there is a lack of consistency in text format and length within the dataset. Future researchers might consider cutting off text to the same word length in all cases or only using summaries written directly in English to avoid possible translation errors. Improvement in feature extraction could also lead to more useful interpretation of the top weighted n-grams used for class predication by indicating topic areas with wider implications for the prosecution of human trafficking cases. Development and testing of Deep Learning models using word embedding feature extraction techniques on this Human Trafficking case dataset would also provide an interesting extension to the work completed in this paper. Finally, the ethical implications of these experiments and any future studies in Legal Judgement Prediction cannot be overlooked. Though the preliminary results of this dissertation project appear to add further support to promising research into the use of NLP machine learning in the legal domain, it is imperative that the distinction between what can be done and what should be done remains at the forefront of all AI research. This is particularly crucial for predictive systems which are developed with potentially life altering implications when applied in the real world. Addressing the recognized bias in the vast majority of collected data is an ongoing problem to the ethically successful implementation of predictive risk analysis systems in both public and private sectors. Algorithms which can successfully predict court judgements in criminal cases, even with a high level of accuracy, are useless if they continue to operate inside wider systems of societal and economic inequality.

By Theresa K. Foster as excerpts from the full dissertation paper submitted for completion of the MSc Data Analytics degree at Oxford Brookes University September 2021 (degree awarded December 2021). See the full Works Cited for the paper below.